Introduction and Summary

Can you run too many miles when training for a marathon? Possibly. The data shows that runners who log more weekly mileage finish faster. Though it's not quite as simple. This post is for the recreational, amateur, and elite runners. We'll explore what separates 4:30 marathon finishers from those who complete it in 2:10.

If short on time, I'd like to leave you with these 7 insights at least to help you on your running journey:

- Prioritize running more frequently rather than simply adding miles.

- Many runners fail on race day because they haven't practiced their target race pace enough, especially on long runs.

- You might be running more miles than necessary for your target finish time.

- Missing just one week of training can significantly hurt your performance.

- Trying to train like an elite runner without their years of background can backfire.

- Take pride in being a recreational or amateur runner, no shame in going slower.

- If only one takeaway: consistent mileage, built gradually over years.

More mileage generally means faster marathon times

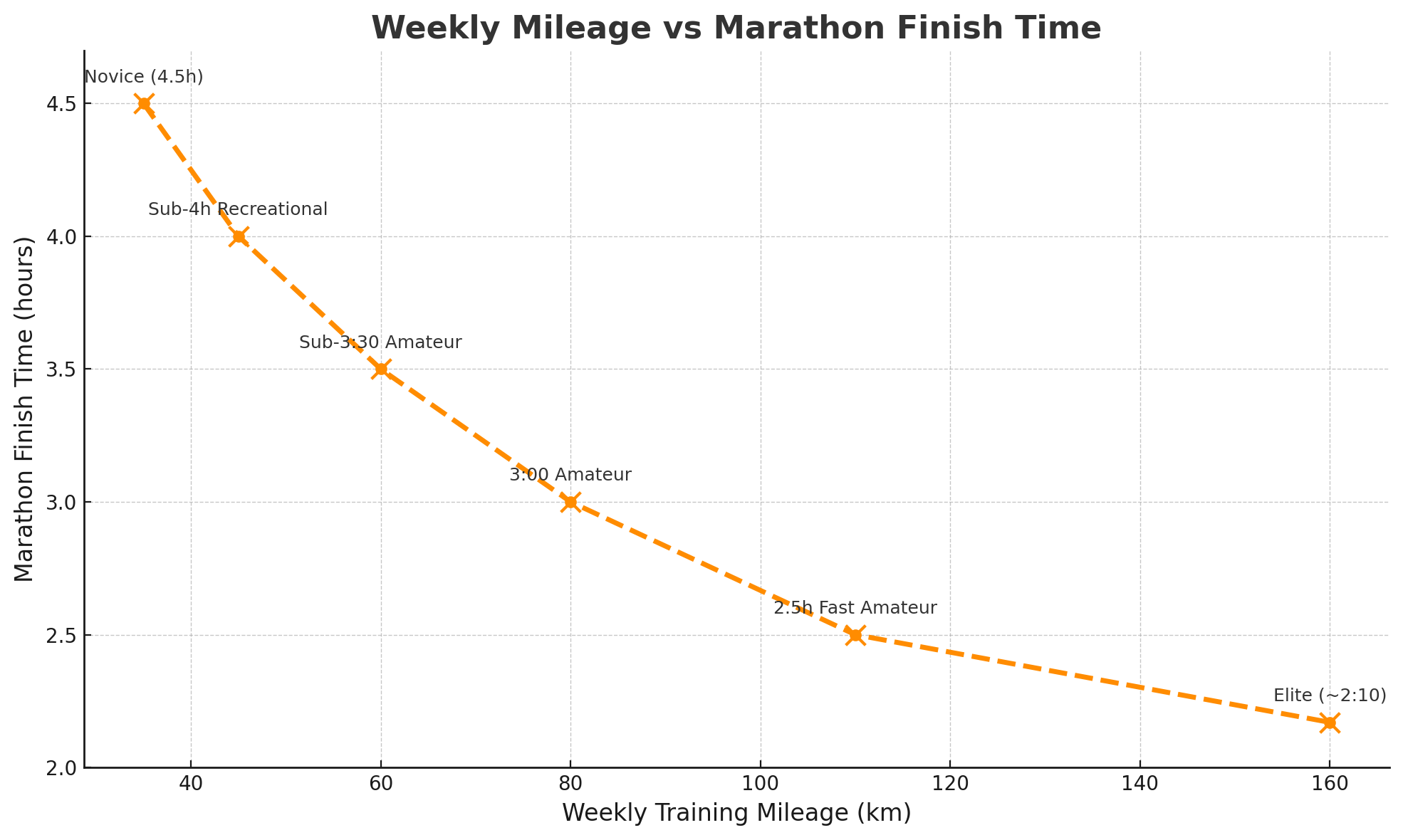

Data from 119,000 Strava marathoners reveals a clear trend: higher weekly mileage usually means faster finish times. For example, runners finishing between 2:00-2:30 hours typically ran about 107 km weekly, while those finishing in over four hours averaged just 35 km per week.

Another study backs this up, showing that increasing weekly mileage from 30 to 50 miles can cut finish times by up to 32 minutes. Beyond 50 miles, gains become smaller.

Surprisingly, many standard training plans suggest more mileage than runners actually need. For instance, runners aiming for sub-4-hour marathons are often told to run about 35 miles per week, but actual sub-4 finishers average closer to 25 miles. This mismatch explains why many runners miss their goals.

Mileage matters because it improves your aerobic fitness, muscular endurance, and running efficiency, all essential for surviving 26.2 miles. Research from European Applied Physiology supports this, highlighting mileage as a key performance factor.

Huge differences between recreational, amateur, and elite runners

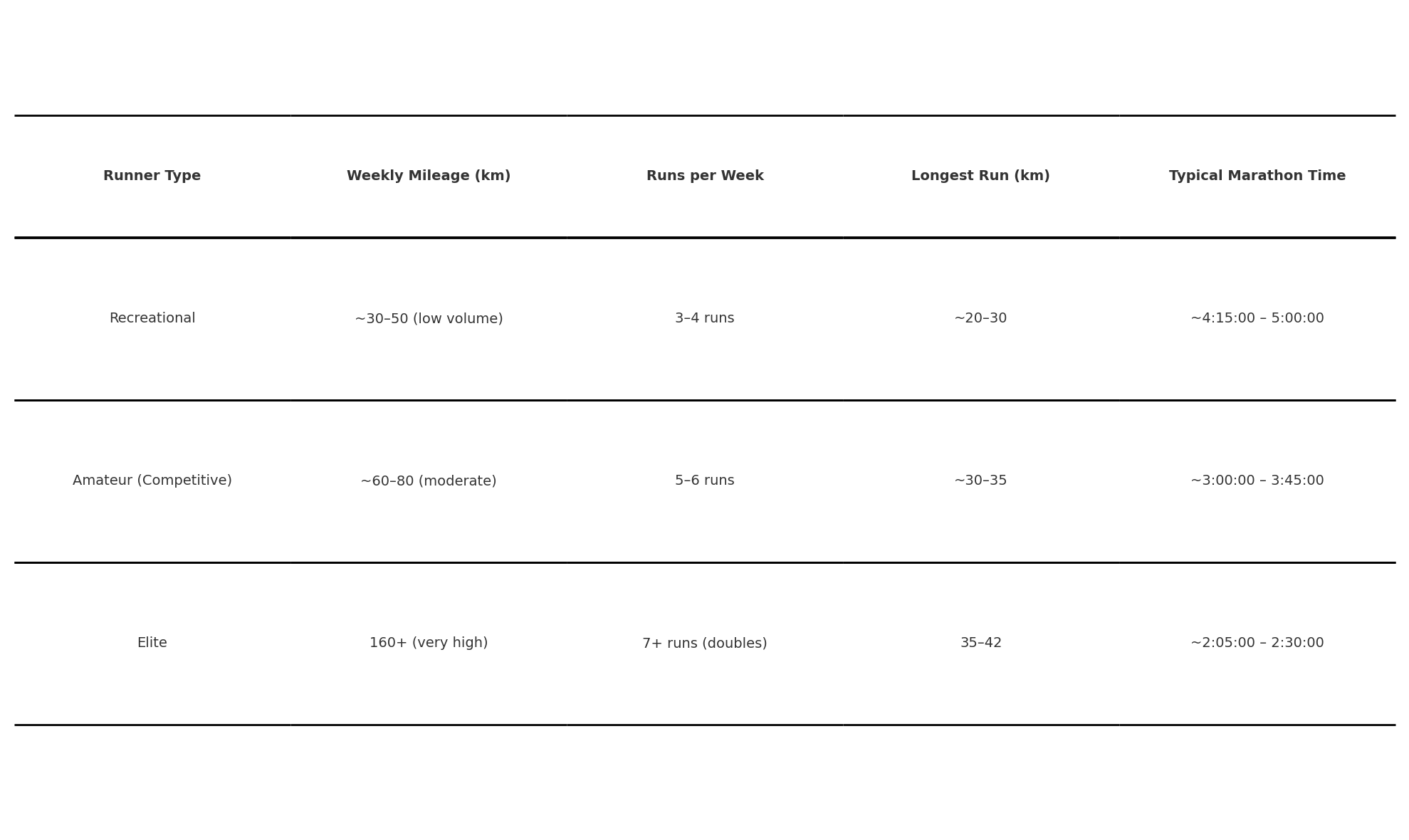

It's helpful to think about marathon runners in three broad groups:

- Recreational runners: Typically finish over 4 hours, run 3-4 days per week, totaling 25-30 miles a week.

- Amateur competitors: Targeting sub-4 or even sub-3 hours, they run 5-6 days weekly, averaging 40-65 miles.

- Elite runners: Professionals clocking marathon times between 2:00-2:30, running daily (sometimes twice a day) and averaging 100-140 miles per week.

Recreational and elite runners are worlds apart. A recreational runner might struggle with 50 km per week, whereas an elite athlete covers that distance in just two days.

Improve frequency before trying elite mileage

While mimicking elite training is tempting, recreational and amateur runners risk injury or burnout by jumping straight to high mileage. Instead, I recommend gradually increasing how often you run each week. Research indicates that runners benefit most by averaging at least 10 km per run and having a weekly long run of 21 km or more. Frequency makes higher volume manageable.

Amateur runners often run 5-6 times per week, while elites might double up sessions, totaling up to 12 runs weekly. Even short breaks (like a week off) can slow down a recreational runner's marathon finish by 5-8%, which can translate to 10-20 minutes for a 4 hour finisher. Consistent, frequent running makes each mile feel easier and improves overall performance.

Genetics matter, but training transforms you

Though genetics, like your body's oxygen uptake capacity (VO₂max), partly determine marathon potential, training significantly shapes performance. VO₂max alone predicts only 59% of marathon outcomes, leaving plenty of room for improvement through training.

Take Paula Radcliffe, former marathon world-record holder, whose running economy improved 15% with training, despite no significant VO₂max change. Consistent mileage builds endurance, muscular efficiency, and raises the lactate threshold, all essential for marathon success.

Elites maintain 80-85% of their VO₂max during races; recreational runners manage about 65-70%. High-volume training closes this gap, allowing runners to hold faster speeds with less fatigue.

Mindful pacing prevents race-day meltdowns

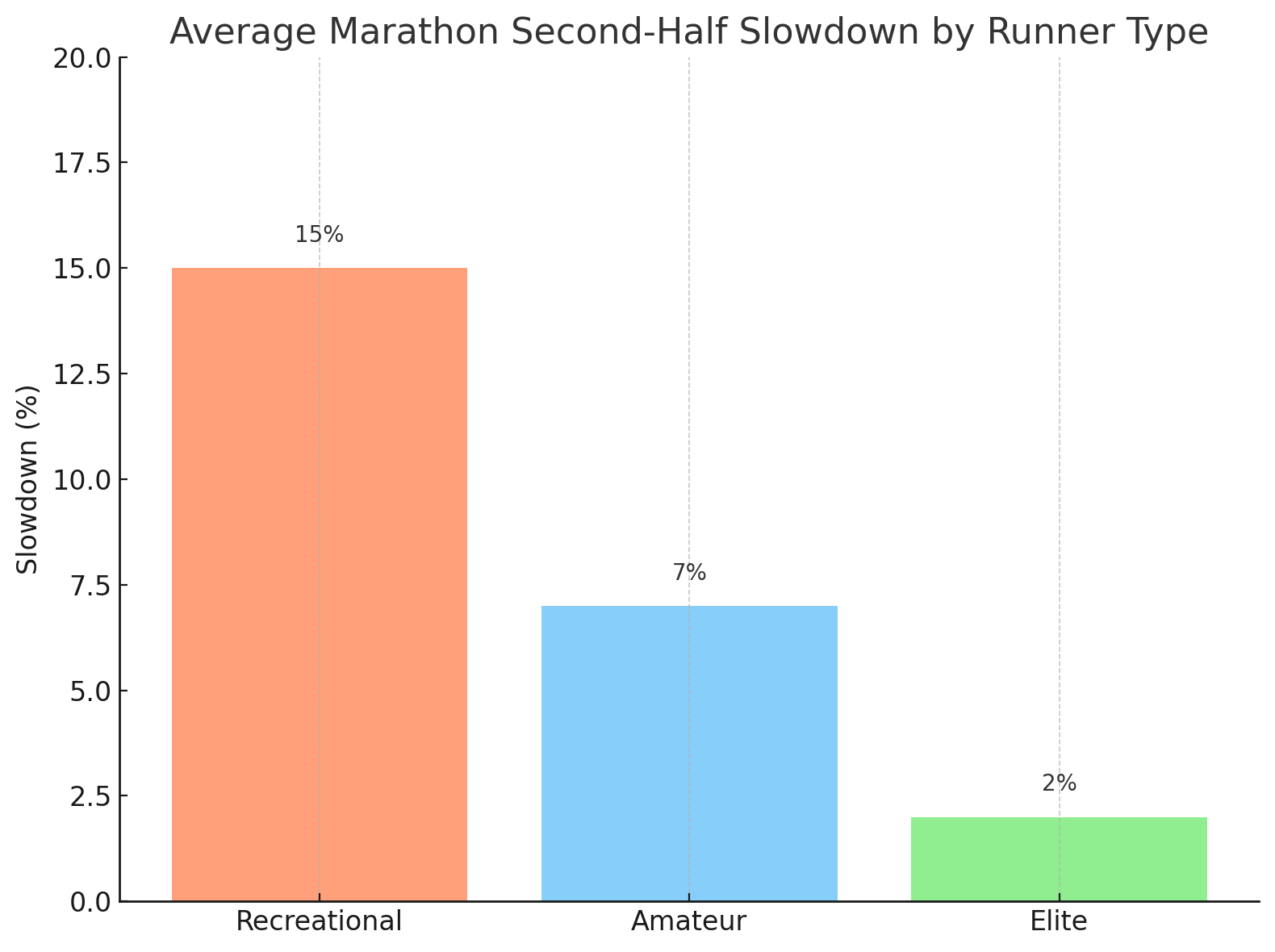

Poor pacing can ruin months of training in a single race. Nearly 90% of marathoners slow significantly in the second half. Mid-pack runners slow by ~15%, slower runners by 17%, while elites often maintain even splits.

Why? Novice runners often start too fast, burn through glycogen early, and hit "the wall." More experienced runners pace more consistently because they've practiced extensively at their goal pace during long runs.

Interestingly, slight slowdowns (positive splits) of 1-3% in the second half might actually indicate ideal pacing for recreational runners. Significant slowdowns (over 10%) mean the initial pace was too aggressive .

So, while elites shooting for world records often execute slight negative splits (because they are highly trained to finish strong), the data hints that the trick is keeping it gentle. The problem for many recreational runners is their fade is far from gentle – it’s very much like hitting a brick wall at 30K.

Training can mitigate these issues. Higher weekly mileage and more long runs at steady effort improve your glycogen stores, fat-burning ability, and mental pacing skills. In a very real sense, higher-volume training not only makes you faster but also makes you fade less. Practice teaches how goal pace should feel at different points, and the body becomes conditioned to hold that pace.

The 80/20 myth

Here's an encouraging insight from the large-scale Strava study: the performance difference between mid-pack runners and top finishers wasn't primarily due to innate speed. It was about training volume. According to the Sports in Medicine study mentioned earlier, faster marathoners didn't perform significantly more intense workouts compared to others; rather, they simply logged many more easy-paced miles. This implies that most runners could see substantial improvements not by drastically increasing their speed during training sessions, but by increasing the overall mileage of their easy runs to build a bigger aerobic foundation.

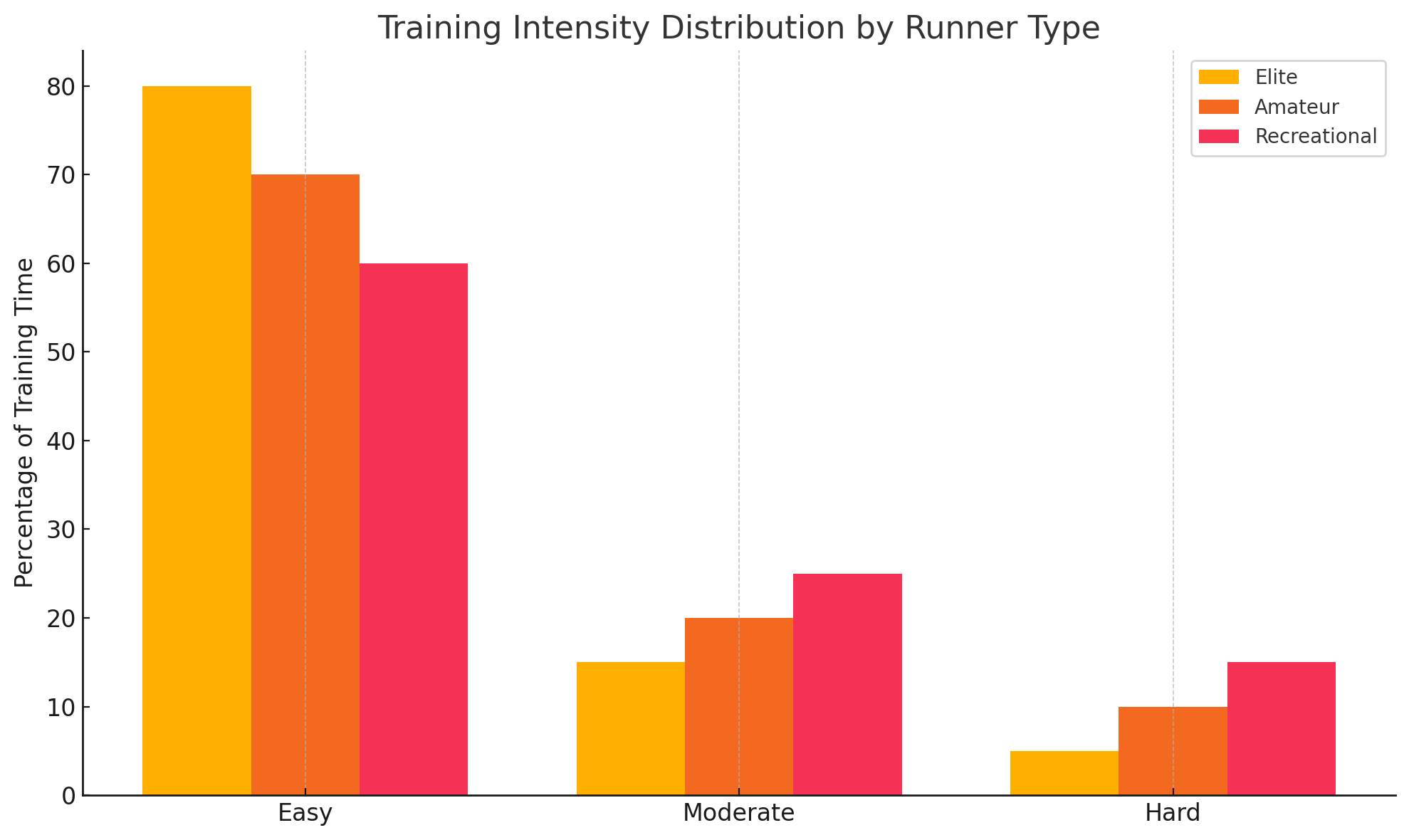

Looking closely at the Strava dataset, most runners followed a pyramidal intensity structure: roughly 80% of their training was spent in Zone 1 (easy effort), 10-15% in Zone 2 (moderate, threshold effort), and just 5-10% in Zone 3 (high-intensity intervals). However, the data reveals a crucial detail. The faster the runners, the greater the proportion of their mileage done at an easy pace. Specifically, the fastest runners devoted about 80% of their total mileage to easy running, whereas recreational runners spent only 50-60% of their mileage in this easy zone.

These statistics clearly illustrate why recreational or amateur runners shouldn't directly copy elite training methods. Many recreational runners mistakenly run too fast on their supposed "easy days." As a result, they end up training in a problematic "gray zone," which isn't slow enough to adequately build aerobic capacity without fatigue, nor fast enough to effectively enhance their speed. Elite athletes, on the other hand, significantly slow down during their recovery runs, often running at paces far slower than their race pace, to ensure they are fully recovered and ready for the next challenging workout.

Ultimately, many recreational runners mistakenly believe that pushing harder on easy days will make them faster. But in reality, this habit only drains their energy and reduces how much total weekly mileage they can handle safely. The fastest marathoners aren't doing anything magical. They're simply accumulating a large volume of running at low to moderate intensity. As running coaches frequently advise, the secret to improvement is straightforward: "keep the hard days hard and the easy days truly easy."

Finding your mileage "sweet spot"

The next logical question is, how much training is enough? Unfortunately, there's no straightforward answer. The ideal point is when you start experiencing diminishing returns; in other words, when adding more mileage doesn't lead to significantly better performance and instead increases your risk of injury or fatigue. Recognizing this point can be tricky and often requires a combination of personal experience, experimentation, and careful attention to your body's signals. Sometimes, you'll need to push your boundaries slightly to find your true limit, but it's crucial to adjust quickly once you sense you've gone too far.

Why should we care about diminishing returns? As you approach your maximum performance potential, every additional minute you shave off your marathon time becomes progressively harder to achieve. Furthermore, higher mileage isn't without drawbacks. It also comes with increased risks of injury and fatigue, which can disrupt your training consistency if not carefully managed. Each runner’s ideal mileage varies significantly. For example, some amateur runners might find that increasing from 80 km/week to 100 km/week only yields marginal improvements but significantly raises their risk of injury. For them, 80 km might be the optimal balance. Meanwhile, others might handle 120 km/week comfortably and continue to see performance benefits.

Sports scientists estimate the sustainable limit for marathon training to be around 120 miles (approximately 190 km) per week. Beyond this threshold, the likelihood of physical breakdown or injury increases significantly. Even elite marathoners, who sometimes push their weekly mileage to these extremes, usually do so only for limited periods. Non-elite runners typically start encountering diminishing returns much sooner, often around 100 km per week, unless they've built up gradually over several years and can properly support their training with adequate rest, nutrition, and complementary exercises.

Eventually, merely adding more slow mileage might become less beneficial compared to introducing strategic elements of speed work or strength training. The good news is you don’t have to choose exclusively between training volume and intensity. Both can coexist effectively. Earlier sections highlighted that runners who regularly include tempo runs or interval sessions tend to gain additional improvements beyond what mileage alone offers. The best strategy is to optimize your weekly mileage to a level you can sustain comfortably, then selectively incorporate higher-intensity sessions to enhance your aerobic capacity and running efficiency.

A marathon is simple, we overcomplicate it

Marathon success can seem like a complicated equation: VO₂ max + mileage + long runs + pacing + xyz = faster marathon time. But in analyzing thousands of runners, a beautifully simple truth emerges: those who commit to consistent, hearty training tend to see the best outcomes. High weekly mileage (mostly easy), sensible long runs, and good pacing habits form a recipe for success across the spectrum of runners. The specifics differ. An elite may run 120 miles/week while a newer runner runs 30, but each is pushing their personal envelope.

The data shows that with each step up in training, big improvements follow. Endurance increases, average pace drops, and finish times plummet. And perhaps most encouragingly, this is largely under our control. Unlike our age or our genes, training is something we can improve deliberately.

Foundational insight: In many cases, the principle separating you from your goal time is the same principle separating mid-pack runners from elites: consistent mileage over time. As the study from Applied European Physiology we saw earlier put it, marathon performance is strongly linked to a runner’s lactate threshold speed, and “training volume is more closely related to lactate threshold than training intensity.” In plain english: train more smart miles > improve your lactate threshold > improve marathon finishes.

Every mile is a deposit in the fitness bank, and come marathon day, you get to withdraw with interest. The elite logging 200 km weeks and the newbie doing 20 km weeks are on the same journey, striving to be a bit better than they were yesterday. The scale is different, but the spirit is the same. And really, you shouldn't be running only for the medal and the seconds.

Closing thoughts

Find your weekly mileage threshold: this threshold is individual. Find yours by incrementally increasing mileage and tracking performance vs. fatigue. Quality should not be sacrificed blindly for quantity once you hit a high level.

The marathon is a race like no other: the marathon rewards what you invest. Unlike shorter races that might favor raw talent or youth, the marathon is an endurance test where training reigns supreme. As the saying goes, “the marathon doesn’t lie.” If you’ve put in the work, the long miles, the tempo runs, the patient easy runs, it will show. And if you haven’t, 42.2 km will expose that lack of preparation.

For anyone reading this and contemplating their next marathon goal, the data should encourage you to dream big but train smart. Identify whether you’re more limited by volume or by consistency or by pacing, and attack that weakness. The experiences of 100,000 runners tell us that improving your training will improve your race.

And thank you for your time.

Further reading

Special thanks to the following authors, websites, studies and researchers, for providing us the valuable information needed to write this article

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39616560/ https://bmcsportsscimedrehabil.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13102-016-0052-y https://marathonhandbook.com/faster-marathon-time-more-easy-miles/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36207466/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29200895/ https://www.dovepress.com/physiological-and-training-characteristics-of-recreational-marathon-ru-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-OAJSM https://blog.runalyze.com/training/how-bad-is-an-interruption-in-marathon-preparation/ https://sportsmedicine-open.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40798-022-00438-7 https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cardiovascular-medicine/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2022.856875/pdf https://medium.com/data-science/the-controlled-fade-b972e11ab452 https://lukehumphreyrunning.com/bonking-and-pacing/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3890068/ https://runningmagazine.ca/sections/training/marathoners-are-your-easy-runs-more-important-than-workouts/ https://marathonhandbook.com/how-much-running-is-too-much/ https://runningfrommyproblems.com/2022/10/24/how-often-do-you-need-to-run-marathon-training/