Training Load vs. Training Stress: What Runners Need to Know

Your watch says you're recovered. Your legs say otherwise.

This disconnect happens because modern running analytics track two fundamentally different metrics that runners often confuse: training load and training stress. Understanding the distinction between these measurements can transform how you approach marathon preparation, recovery planning, and race day performance.

The Core Difference: What Load and Stress Actually Measure

Training load quantifies the work you're doing. It's an objective measure of volume and intensity combined into a single number. Think of it as the mechanical stress you're placing on your body through distance, pace, and effort.

Training stress, by contrast, measures your body's response to that work. It incorporates physiological signals like heart rate variability, resting heart rate, sleep quality, and perceived fatigue. This metric attempts to capture the biological cost of your training.

Consider two runners logging identical weekly mileage at similar paces. Runner A sleeps eight hours nightly, eats well, and manages work stress effectively. Runner B gets five hours of sleep, skips meals, and battles a demanding deadline. They share the same training load. Their training stress diverges dramatically.

How Training Load Is Calculated

Most running platforms calculate training load using variations of the Training Impulse (TRIMP) method, developed by exercise scientist Eric Bannister in the 1970s. The basic formula multiplies training duration by intensity, then applies a weighting factor based on heart rate zones or perceived effort.

A simplified version looks like this: Training Load = Duration × Intensity Factor.

A 90-minute easy run at 65% max heart rate generates less load than a 60-minute tempo run at 85% max heart rate, even though the tempo run is shorter. The intensity weighting makes the difference.

Platforms like Strava, Garmin, and Polar each use proprietary algorithms, but the underlying principle remains consistent. They're measuring the stimulus you're applying, not how your body processes that stimulus.

Recent research published in the Journal of Applied Physiology found that training load calculations correlate strongly with performance improvements when monitored over 12-week training blocks. Runners who gradually increased their weekly training load by 10-15% showed better race outcomes than those with erratic load patterns.

Understanding Training Stress: The Body's Response

Training stress metrics attempt something more ambitious. They want to quantify recovery need, injury risk, and readiness to train hard again.

Garmin's Training Status uses a combination of acute training load (last week), chronic training load (last month), and heart rate variability to generate categories like "Productive," "Maintaining," or "Overreaching." Whoop calculates a Recovery Score using HRV, resting heart rate, respiratory rate, and sleep data.

These metrics incorporate variables beyond your control during runs. Poor sleep tanks your training stress score even if you didn't run that day. A stressful work presentation elevates your resting heart rate, signaling reduced readiness.

The critical insight here involves recognizing that training stress reflects total life stress, not just running stress. Your body doesn't compartmentalize. The cortisol from a bad night's sleep affects your muscle recovery just like the cortisol from a hard interval session.

The Acute-Chronic Workload Ratio: Bridging Both Concepts

One of the most useful frameworks for marathon runners combines elements of both load and stress: the Acute-Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR).

ACWR compares your recent training load (typically the last week, called acute load) against your longer-term average (usually four weeks, called chronic load). The ratio reveals whether you're ramping up training faster than your body can adapt.

Research across multiple sports, including a comprehensive study of over 2,000 athletes published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, suggests that an ACWR between 0.8 and 1.3 represents the "sweet spot." Below 0.8, you're potentially detraining. Above 1.3, injury risk increases substantially.

Here's what this looks like in practice. Imagine your average weekly training load over the past month is 400 training load units. This week, you logged 480 units. Your ACWR is 1.2, which falls within the optimal range. Your body has sufficient chronic training load to handle the acute spike.

Now imagine your chronic load is 300 units and you suddenly jump to 450 in one week. Your ACWR hits 1.5. You've outpaced your body's adaptation capacity, even though the absolute load isn't excessive.

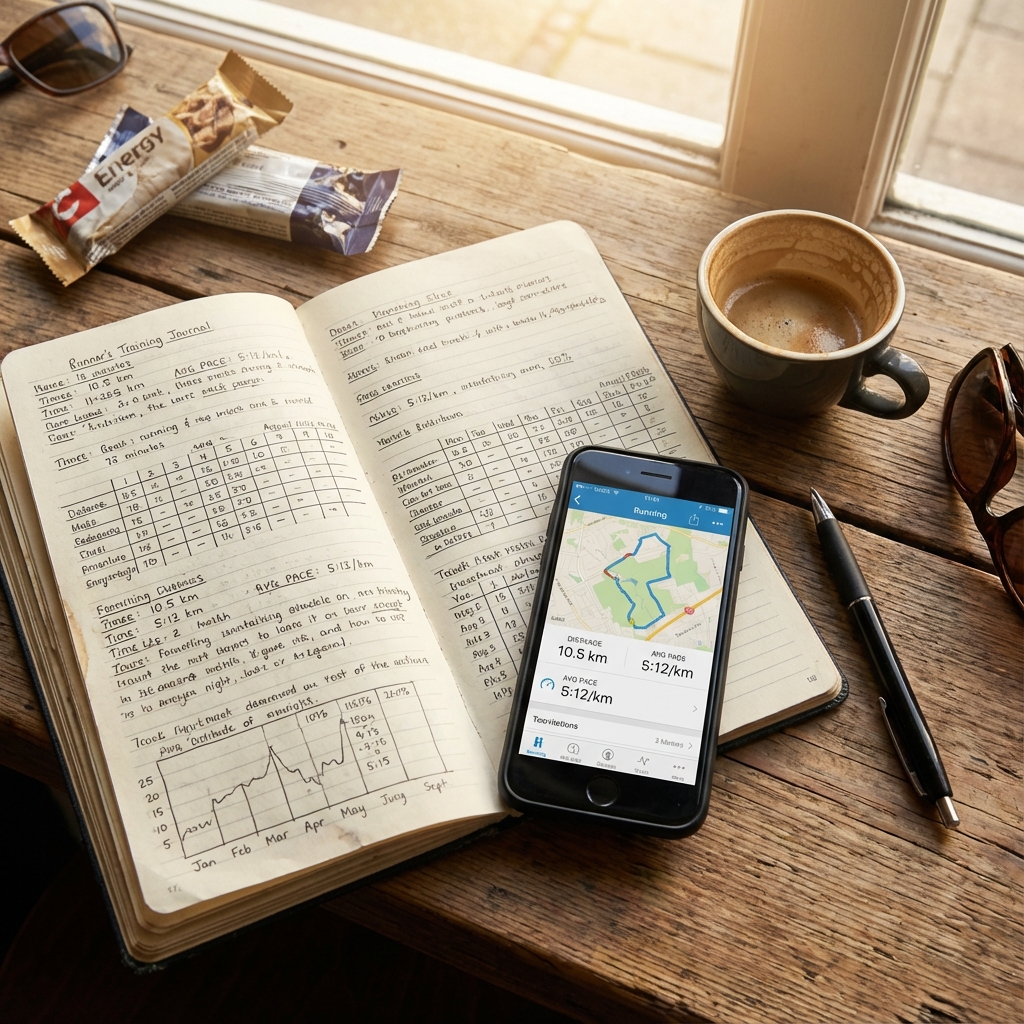

Many running platforms now include ACWR or similar metrics. Runner Tools & Calculators can help you track these ratios and plan appropriate training progressions.

Practical Applications for Marathon Training

Understanding the load-stress distinction changes how you structure training blocks.

Use training load for planning progressive overload. When designing your 16-week marathon buildup, focus on gradually increasing weekly training load by 10-15%. This ensures systematic progression that challenges your aerobic system without overwhelming it.

Use training stress for daily training decisions. Your watch shows low HRV and elevated resting heart rate? That's high training stress signaling reduced readiness. Convert today's planned tempo run into an easy aerobic effort, maintaining training load while respecting physiological stress.

Monitor the gap between load and stress. When training load increases but training stress remains manageable, you're adapting well. When load stays constant but stress climbs, external factors are compromising recovery. You need more sleep, better nutrition, or stress management, not different workouts.

Pay attention to non-running stressors. A demanding work week, poor sleep, or relationship stress all elevate training stress without adding training load. During these periods, you may need to reduce training volume by 20-30% to maintain the same total stress level.

Common Mistakes Runners Make

The most frequent error involves treating training stress scores as definitive judgments rather than informational signals. Your watch says you're recovered, but your legs feel heavy. Trust your legs. The watch captures useful data points but can't fully assess your readiness.

Another mistake involves chasing training load numbers without considering training stress. Hitting your planned weekly mileage matters less than accumulating that mileage while maintaining manageable stress levels. A runner who completes 85% of planned training load with low stress will outperform someone who hits 100% while chronically overstressed.

Some runners make the opposite error, obsessing over stress metrics and pulling back from planned training whenever scores look suboptimal. Training requires stress. The goal involves applying appropriate stress that stimulates adaptation, then allowing adequate recovery. Perfect readiness isn't the objective. Progressive adaptation is.

Integrating Both Metrics Into Your Training

The most effective approach uses training load for macro planning and training stress for micro adjustments.

Start your training cycle by mapping out progressive load increases week by week. Use historical data or established guidelines. A runner averaging 50 miles weekly might plan to build toward 70 miles over 12 weeks, adding 5-10% load weekly.

Within that framework, let training stress guide daily decisions. High stress with a hard workout scheduled? Shift the workout back a day and insert an easy run. Low stress after a rest day? Proceed with confidence.

Monitor the relationship between the two metrics weekly. Training load increasing while stress remains stable indicates positive adaptation. Load stable but stress climbing suggests inadequate recovery or non-running stressors requiring attention.

External research from the European Journal of Applied Physiology tracking 50 marathon runners through 16-week training blocks found that runners who adjusted training based on both load progression and daily stress metrics showed 23% fewer overuse injuries compared to runners following rigid plans.

The Bottom Line

Training load tells you what you're doing to your body. Training stress tells you what your body thinks about it.

Both metrics provide valuable information, but neither tells the complete story alone. Training load helps you plan systematic progression. Training stress helps you execute those plans while respecting your body's current capacity.

The smartest approach involves planning your training around progressive load increases, then making daily adjustments based on stress signals. This combination ensures you're challenging your aerobic system appropriately while allowing adaptation to occur.

Your marathon performance depends not on accumulating the highest possible training load, but on accumulating sufficient load while managing training stress effectively. The runners who master this balance show up on race day with developed aerobic systems and fresh legs.

That's the real advantage of understanding these metrics. You stop training randomly and start training strategically, applying appropriate stress that drives adaptation without breaking down your body. You learn to distinguish between challenging yourself and overwhelming yourself.

The goal involves getting stronger, not just doing more. These metrics help you tell the difference.